Jacinta Corcoran

Submitted to

Department of Social Sciences, Technological University Dublin in partial fulfilment of

the requirements leading to the award of Masters of Arts in Mentoring Management

and Leadership in the Early Years

Word Count:13,964

Technological University Dublin.

Declaration of Ownership

I declare that the attached work is entirely my own and that all sources have been

acknowledged.

Signature:……………………………………….. Date:…………………………………………………………

Submitted to the Department of Social Sciences TU Dublin, in partial fulfilment of the

requirements leading to the award of M.A. Mentoring Management and Leadership in the

Early Years.

Word Count:

Technological University Dublin April 2019

Acknowledgements

Primarily I would like to express my sincere gratitude to all the participants who made time

within their busy schedules to contribute to this study and share their experience.

I also wish to acknowledge and thank my supervisor Emma Byrne MacNamee for her

professional support and guidance.

Finally, I would like to thank my family Eoghan, Lochlainn and Tiarnán for their continued

understanding and support.

Table Of Contents

Title Page

Declaration of Ownership

Acknowledgements

Table of Contents

List of Tables and Figures

Abbreviations

Glossary of Terms

Abstract

Chapter one: Introduction

1.1 Introduction

1.2 Aims and Objectives of study

1.3 Rationale

1.4 Outline of study

Chapter two: Literature Review

2.1 Introduction

2.2 Prevalence

2.3 Theoretical Framework

2.4 Impact of Homelessness on Children and Families

2.4.1 Adversities preceding homelessness

2.4.2 Adversities faced as a result of becoming homelessness

2.4.3 Adversities associated with service system response

2.5 Policy Response to Homelessness

2.6 Policy response to early years education

2.7 Implications for Provision of early Years Care and Education

2.8 Leadership

2.9 Conclusion

Chapter three: Methodology

3.1 Introduction

3.2 Research Approach

3.3 Research Instrument

3.4 Sample and Access

3.4.1 Sample

3.4.2 Sample Method

3.4.3 Rational for target population

3.5 Data Collection

3.6 Limitations of Study

3.7 Ethical Issues

3.8 Reflexivity

3.9 Data Analysis

3.10 Conclusion

Chapter four: Presentation of Findings

4.1 Introduction

4.2 Engagement

4.2.1 Types of Homeless Accommodation

4.2.2 Impact of Homelessness on Children

4.2.3 Contributory Factors

4.2.4 Stigma, Fear and Isolation

4.3 Service Provision

4.3.1 Resources

4.3.2 Statutory Funding

4.3.3 Staffing

4.4 Impact on Staff

4.41 Emotional Cost

4.42 Changing Manager Role

4.4.3 Changing Role of Early Years Service

4.5.4 Conclusion

Chapter five: Discussion

5.1 Introduction

5.2 Engagement

5.2.1 Pathways to Homelessness

5.2.2 Understanding Impact of Homelessness

5.3 Service Provision

5.3.1 Resources

5.3.2 Funding

5.3.3 Staffing

5.4 Impact on Staff

5.5 Recommendations

5.5.1 Policy

5.5.2 Practice

5.5.3Research

Conclusion

References

Appendices

Appendix 1 Interview Protocol for Early Years Service Managers

Appendix 2 Interview Protocol for Development Officer Working for a Government

Funded Company Providing Support to Early Years Services.

Appendix 3: Letter to participants

Appendix 4: Participant Consent Form

Appendix 5 Sample Interview transcription

List of tables

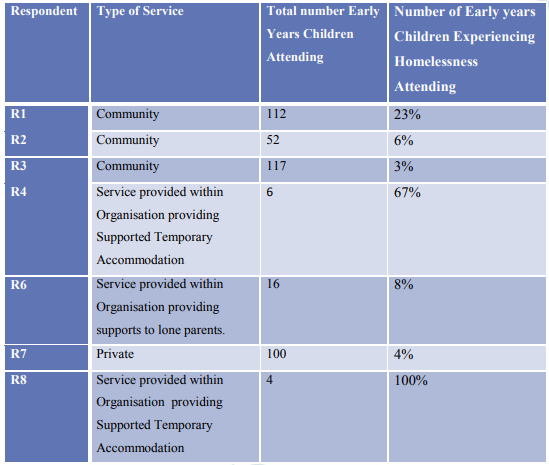

Table 1 Overview of number children accessing services

Abbreviations

ABC Area Based Childhood Programme

A&E Accident and Emergency Hospital Care

B&B Bed and Breakfast Accommodation

CCSRT Community Childcare Subvention Resettlement (Transitional)

CCSP Community Childhood Subvention Plus

CECDE Centre for Early Childhood Development and Education

CPD Continuous Professional Development

CSO Central Statistics Office

DCYA Department of Children and Youth Affairs

DES Department of Education and Skills

ECCE Early Childhood Care and Education Programme

NCCA National Council for Curriculum Assessment

Glossary Of Terms

Area Based Childhood Programme Targeted additional investment in evidencebased early interventions

to improve the longterm outcomes for children and families living

in areas of disadvantage.

Access and Inclusion Model (AIM) A programme of supports designed to ensure

that children with disabilities can access the

ECCE Programme in mainstream pre-school settings.

Better Start Quality Development Service National early years quality development

support service for early years education and care providers

Family Hubs Supported temporary accommodation arrangements intended to facilitate more

coordinated needs assessment and support planning including on-site access to required

services, such as welfare, health, housing services, and appropriate family supports and

surrounds.

Circle of Security Parenting programme aiming to help parents understand their child’s emotional world

enabling them to help their children manage their emotions and develop self -esteem and

sense of security.

City & County Childcare Committees There are 31 CCCs who operate as local agents of DCYA and support the delivery of early

education and childcare programmes at a local level. Services include Advice, support and

training for providers and information in relation to services and networks for parents.

CSSR(T) Community Childcare Subvention Resettlement (Transitional) Programme. As part of the

“Rebuilding Ireland – an Action Plan for Housing and Homelessness” the DCYA has

provided access to free childcare for children of families experiencing homelessness.

ECCE Early Childhood Care & Education Programme

(ECCE) – provides early childhood care and education for children of pre-school age (over

three and not more than 5 and a half years old). A capitation fee is paid by the state to

participating Early Childhood Education services that provide a pre-school service free of

charge to all children within the qualifying age range.

Family Hubs supported temporary accommodation arrangements intended to facilitate more

coordinated needs assessment and support planning including on-site access to required

services, such as welfare, health, housing services, and appropriate family supports and

surrounds

Highscope Model of education designed in U.S.A promoting high quality equitable educational

programmes to promote positive outcomes for children and young people.

Meitheal A case co-ordination process for families with who require multi-agency intervention but who do

not meet the threshold for referral to the Social Work Department under Children First.

Practitioners in different agencies can use and lead on Meitheal so that they can communicate and

work together more effectively to bring together a range of expertise, knowledge and skills to meet

the needs of the child and family within their community.

Abstract

Homelessness in Ireland has increased rapidly over recent years with children and families making up increasing proportions of the numbers recorded whilst single parent families are representing a disproportionate number of families experiencing homelessness. Consequently many early years services are supporting unprecedented numbers of children who are experiencing homelessness to engage and fully participate in early education programmes.

The experience of homelessness can permeate many levels and various aspects of a child’s life particularly when historical risks and adversities are to be factored. Within this context this study guided by an ecological framework explores the range of influences on the experiences of children and their families during periods of homelessness and early years service providers responding to the needs of children experiencing homelessness.

Guided by a qualitative approach Semi structured interviews were carried out with early years service managers and a development officer working for a government funded company providing support to early years service providers to explore what approaches early years services are adopting while responding to the needs of children experiencing homelessness.

Findings show despite many challenges early years services face those who work in the sector and in particular for the purposes of this study, early years managers are incredibly committed to their role maintaining the highest standards for all children using their service while acknowledging that children and families experiencing homelessness possess a set of unique needs that may need a unique approach

Introduction

1.1 Introduction

This study explores provision of early years care and education to children who are experiencing homelessness identifying available resources and capacity of a number of early years services. The perspectives of early years service managers is explored identifying supports and challenges observed while responding to the needs of children experiencing homelessness.

This opening chapter sets out the Aims and objectives of the study, illustrates the rationale for the research and provides an outline of the study.

1.2 Aims And Objectives

The overall aim of the study is to explore the perspectives of early years managers in relation to their role in the provision of early years care and education while responding to the needs of children who are experiencing homelessness. In particular it will address the following research questions.

- What role do early years services have in responding the needs of children

experiencing homelessness? - What models of engagement are currently being used by services?

- What are the challenges for early years services responding to the needs of children

experiencing homelessness? - What impact has responding to the needs of children experiencing homelessness had

on management structures and approaches to service provision?

1.3 Rationale

This study is undertaken amid a national housing crisis where despite government policy response within the Rebuilding Ireland Action Plan for Housing and Homelessness the numbers of those being recorded as homeless continues to grow. Families are the currently the fastest growing group presenting as homeless with a disproportionate number of one parent families recorded. A recent study on the educational needs of children experiencing homelessness and living in emergency accommodation (Scanlon & Mc Kenna 2018) identifies that many schools and early years services are providing opportunities for increasing numbers of children experiencing homelessness to fully engage with education. A number of critical areas were identified as requiring support for teachers to meet the childrens educational needs including access from agencies, specific funding to support pupils training and coordination of services. Although early childhood professionals were included in the sample the low response rate to the quantitative surveys provided limited insights to early years providers who are working with children in emergency accommodation.

Parallel to the homeless crisis is a staffing crisis within the early childhood care and education sector wrought with underinvestment, high staff turnover due to burnout and an exodus of qualified staff from the sector and sustainability issues for services (House of the Oireachtas 2017) Despite recent responses by policy to enhance access and quality of service provision through funding initiatives for childcare places, and training for practitioners the number of graduates leading the workforce remains considerably lower than the EU recommended level required for quality provision. This is significant in view of the relationship between qualifications and improved outcomes for children particularly children from disadvantaged families (Sylva, Melhuish, Sammons, Blatchford & Taggart 2004)

In consideration of the above points this topic presented to the researcher who within their role works with children and families who have experienced homelessness, as an interesting and under researched area. In exploring how services are currently responding and what challenges they are meeting while engaging with children and families experiencing homelessness may inform how services provide supports in the future to ensure provision for the diverse and changing needs of children and families particularly the most vulnerable.

1.4 Outline Of The Study

Chapter one provides an outline of the study presenting the rationale for the research and illustrating the aims and objectives of the study.

Chapter two will present the literature. Firstly prevalence of children and families currently experiencing homelessness in Ireland will be presented to highlight the severity of the homeless crisis and how it impacts the early years sector. Literature discussing the impact of homelessness on children from a national and international perspective will be presented keeping in mind an ecological framework. Current policy in relation to housing will be briefly introduced followed by an exploration of policy in relation to early childhood care and education. Finally implications for service provision and the role of the manager will be represented.

Chapter three will outline the methodology used discussing research design and detailing research methods used. The sampling method and sample will be presented and data analysis methods used described.

Chapter four will present the findings from eight semi structured interviews seven of which were undertaken with managers of early years services and one with a development officer from a government funded company providing support to early years service providers. The interviews were completed within three weeks in January 2019. Findings will be presented under three main headings engagement, service provision and impact on staff. A number of sub headings are also included.

Chapter five discusses the key outcomes from the findings in relation to the literature review and the aims and objectives of the study. Recommendations are made based on these outcomes and are also presented. A conclusion will be drawn to the study.

Literature Review

2.1 Introduction

There have been many changes in recent years in relation to policy and legislation in Ireland regarding the provision of early childhood Care and education. While changes have been implemented to promote accessibility and quality, managers as a consequence are faced with complex challenges in relation to workforce, finance and service delivery. Managers are presented with further challenges in relation to the development of service provision due to the diverse social cultural contexts within which children and their families are living. Increasingly early years services are supporting children who are experiencing homelessness as a changing homeless dynamic sees increasing numbers of families becoming homeless and entering emergency accommodation (Department of the Environment, Community and Local Government 2016).

This literature review will highlight the relevant research in relation to early years services responding to the needs of children experiencing homelessness. Firstly the research will explore homelessness, it’s prevalence and impact on young children and their families. This will be followed by a brief description of policy response in relation to homelessness and a policy response to early education. The research will present implications for early years care and education provision following implementation of these policy responses

Finally the research will explore the implication for the early years managers role and leadership within the service implementing policy responses and responding to the needs of children experiencing homelessness.

2.2 Prevalence

In order to measure homelessness it is necessary to consider it’s definition. In an Irish context under the Housing Act 1988, a person is considered homeless if there is no accommodation available which, in the opinion of the local authority would be suitable accommodation for them and whoever might be reasonably be expected to reside with them. It takes into account those accommodated in emergency accommodation, hospitals and night shelters and in the opinion of the authority those unable to provide accommodation from their own resources (Irish Statute Book 1988). The omission of those residing with family may be problematic in relation to creating a comprehensive picture of the issue and for those hidden homeless to access supports. The phenomenon of Homelessness is complex and often a combination of a number of factors. These include structural factors such as lack of affordable housing, unemployment, poverty and personal factors such as relationship breakdown, addiction and mental health. Structural economic factors are seen as the main force of the current homelessness crisis in Ireland. (Government of Ireland 2016, Hearne & Murphy 2017, Focus Ireland 2018).

The past three years has seen a rapid increase in the numbers of people experiencing homelessness in Ireland. Included in the 9,724 individuals reported homeless in Oct 2018, which was an increase of 17% from Oct 2017, where 1,709 families and 3,725 children who were accessing emergency accommodation (Department of Housing, Planning and Local Government 2018). One in every three people homeless being a child (Focus Ireland 2018). Of 23 families surveyed during December 2017, 56 children were included, 42% of which were four years or younger (Focus Ireland 2017). During the last census in 2016, 765 children aged 0-4 years represented the largest group of child age category recorded as homeless (CSO 2016). It is also important to note that national homeless figures do not include those who may be sleeping rough, living in squats, staying with friends or women and children staying in refuge accommodation (Focus Ireland 2018).

Due to this crisis many early years services and schools are supporting unprecedented numbers of children who are experiencing homelessness to engage in services and schools and fully participate in education and are doing so without additional resources or guidance (Scanlon & Mc Kenna 2018).

2.3 Theoretical Frameworks

Children experiencing homeless, while sharing similar needs to children within families living in more stable accommodation have additional unique needs. Furthermore homelessness may intensify these needs and generate new stressors. It may be additionally challenging for children experiencing homelessness to have basic needs met such as physiological and safety needs and the need for belongingness, love, esteem and self – actualization as proposed by Maslow (1943) being fundamental to healthy growth. In exploring childrens needs and how they are met it is useful to consider how they are closely linked to the realities of their parents and families under Bronfenbrenner’s bio-ecological perspective (Swick 1999). This perspective considers the many systems in which the family are engaged and reflects the dynamic nature of family relationships. By understanding the needs and strengths of families they may be supported and empowered during periods of stress such as that experienced during periods of homelessness (Swick & Williams 2006). As explained by Bronfenbrenner, human development or “lasting change in the way in which a person perceives and deals with his environment” (Bronfenbrenner 1979 p.3) occurs within a number of systems. The micro system or the inner most level may present to the child as the family or the early years service and where the child initially learns about their world. Relationships between settings in the micro system as they interconnect in a number of forms such as communication between the settings and the knowledge and attitudes by the settings in relation to each other are important as children have opportunity to engage with caring adults other than parents (Swick & Williams 2006). Contexts experienced within the exosystem may be positive or negative for the child depending on the experience of the adult. For example parents experiencing excessive stress related to work or issues that accompany homelessness such as constant searching and uncertainty related to finding accommodation which indirectly impacts negatively on the child. It may also be the experience of a positive quality early years programme empowering the whole family. Influences within the Macro system such as culture, beliefs, values and political policy influence how we behave and develop, as early years services planning programmes responding to the needs of children and families doing so within legislation and policy which informs early years care and education provision.

2.4 Impact Of Homelessness On Children And Families

Being aware of these dynamic and interactive systems which impact on family functioning may provide a framework for early years providers delivering support for children and their families. Families may have experienced a variety of problems that preceded or contributed to their becoming homeless while also experiencing new problems on entering homelessness (Halpenny, Keogh & Gilligan 2002). Further adversities may present as a consequence to supports implemented to address the immediate needs of children and families (Kilmer, Cook, Crusto, Strater & Haber 2012). Understanding the context and the impact of these problems will further help early years providers apply appropriate support to meet individual child and family needs.

2.4.1 Adversities preceding homelessness.

Children and families may have faced adversities which preceded homelessness and which impact on the child parent relationship. In addition to lack of affordable housing other stressors such as, overcrowding, family conflict, poverty, addiction, and domestic violence may be present (Halpenny, Keogh & Gilligan 2002). Trauma during childhood and parent mental health or separation from a parent, have also been noted as contributory factors to pathways to homelessness (Lambert, O Callaghan & Jump 2018). Experiencing poverty may not only prolong homelessness but may also intensify other related problems (Swick & Williams 2010). Furthermore within families living in poverty parents are more likely to be less nurturing and children more likely to present with behaviour difficulties and depression (Kilmer et al 2012). Teenage mothers are more likely to become homeless than their peers who don’t have children often dropping out of school early leading to poverty and without the support they require to foster positive relationship with their child (Swick and Williams 2010). Also impacting on their capacity to develop quality parent child relationships is their personal history in relation to family disruption during childhood, lack of supportive relationships and abuse. This is of critical significance given that it is recorded that women account for 41% of homeless adults in Ireland and represent 86% of the total number of lone parent households. They are more likely to experience hidden homelessness as they avoid homeless services that may not be female appropriate or are uncounted as they are residing in refuge accommodation following a domestic violence experience (Focus Ireland 2019).

2.4.2 Adversities faced as a result of becoming homelessness.

The experience of becoming homeless may be traumatic and expose children and families to further trauma impacting on “how children and families think feel, behave cope and relate to others” (Guarino & Bassuk 2010 p. 14). The prevalence of traumatic stress among families who are homeless is particularly high. With new threats or dangers becoming reminders of past trauma, families experiencing trauma may be constantly on guard and engaged in emergency fight, flight or freeze responses which may affect thinking, planning problem solving and managing emotional states which impact on relationships (Guarino & Bassuk 2010). Trauma or exposure to household dysfunction or abuse during childhood is also linked to risk factors in relation to disease, quality of life, health care utilization and mortality (Felitti, Anda, Nordenberg et al. 1998). As children and families remain in emergency accommodation for extended periods often under poor conditions many aspects of their lives are impacted including health, well-being, development and education (Halpenny, Keogh & Gilligan 2002).

Inappropriate amenities in emergency accommodation such as poor heating and cooking facilities, overcrowding, lack of play space may aggravate existing or increase the risk of health problems. Temple Street Children’s University Hospital reported an increased number of children presenting to their emergency department who are homeless with 842 recorded for 2018 and with the majority of the 260 admitted between October and December 2018 having presentations attributed to unsuitable cramped temporary accommodation (Temple Street Children’s University Hospital 2019). Mental health issues such as anxiety, stress, emotional and behavioural disorders and developmental delays are exacerbated. Daily routines are affected as restrictions may be placed on access to accommodation during the day or where lack of space and privacy lead to families being out and about for long periods resulting in children experiencing exhaustion. Long periods spent within confined space may lead to conflict and stress among parents. (Keogh, Halpenny, & Gilligan 2006).

Many families experience isolation when placed in accommodation which allows minimal contact with extended family and friends due to the distance and with no visitors policies in place. This disconnection impedes access to natural supports in the community, also impacting negatively on minority families interrupting their cultural norms of social connectedness (Kilmer et al 2012). Living in the same place for short periods prevents parents building relationships with other parents and therefore may miss out on the experience of that support network (Keogh, Halpenny & Gilligan 2006). Homelessness has particular impact on childrens sense of identity, security and sense of place in the community (Guarino & Bassuk, 2010, Swick 1999).

Public perception or actions toward families experiencing homelessness may highlight stigma that is present among employers, school and also among the professionals within services in place to support families. Stigma may be more personal in the form of self blame and shame. Children may be afraid to tell others where they live because they are embarrassed. The fear of rejection or stigmatisation by peers may impact relationships and further magnify the feeling of isolation (Keogh, Halpenny & Gilligan 2006).

Parenting capacity may be challenged during periods of homelessness as barriers present impacting ability to provide a safe nurturing environment where healthy emotional attachments with their child can be developed and where access to resources to further empower the family are limited. Parental self esteem is crucial in the development of healthy parent child relationships (Swick & Williams 2010) but may be affected during periods of homelessness as parents experience loss of control over daily routine and feel judged by their status. Homelessness generates a stressful environment for parenting where parental attention is diverted to managing the instability of accommodation and uncertainty of everyday life and where significant stress may make it furthermore challenging to escape homelessness (O’ Carroll 2012).

Homelessness impacts on educational access and participation across four domains, basic physiological needs, safety, routine and predictability, friendship, trust and belonging and attitudes to school and educational aspirations (Scanlon & Mc Kenna 2018). Many challenges may be faced by families maintaining consistent educational experiences including having to travel long distances and associated costs. Children may have to wake up earlier and return home later impacting on sleep routines. Despite the challenges to homeless families maintaining attendance at school it may be the only source of consistency or stability in the child’s daily routine serving as a support enabling them to cope with instability and insecurity (Keogh, Halpenny & Gilligan 2006, Scanlon & Mc Kenna 2018).

2.4.3 Adversities associated with service system response.

Responses while designed to meet the immediate needs of children and families entering homelessness may unintentionally compound the experience and cause more harm (Kilmer et al 2012). With lack of housing options families may be forced to avail of family hubs where there is a danger that while they are a temporary solution they may become a permanent feature as families remain in this accommodation for excessive periods of time. The risk associated with this being that families may become institutionalised restricting capacity to have normal family lives where functioning in relation to parenting, child development, employment, education and maintaining family networks is inhibited leading “ to a form of therapeutic incarceration” (Hearne & Murphy 2017p. 2) with society over time blaming these families for a situation they did not cause. Hearne & Murphy (2017) further caution that in particular hubs may become the new institutionalisation of vulnerable women and children who, when the failure of the housing market has been forgotten about, will become the problem that needs to be solved.

Stereotypical views of homeless parents by others as lacking in competence may result in their strengths being overlooked and if these views are held by individuals they encounter within services they access it may lead them to underuse valuable resources required to address their needs and impede their empowerment (Swick, Williams & Fields 2014).

2.5 Policy Response To Homelessness

Government Homeless policy has been led by a housing first approach for some time. Rebuilding Ireland (Government of Ireland 2016) the Action Plan For Housing and Homelessness people sets out a specific aim to increase efforts and resources towards providing those experiencing homelessness with a home following a housing led housing first approach. It prioritises the need to address the level of homeless families and those who are long term homeless living in emergency accommodation. It proposes rapid delivery housing alongside additional measures which would prevent others from losing their homes, improving the rental sector and utilizing existing housing. The plan acknowledges issues that may arise in relation to school attendance for children who are experiencing homelessness (Government of Ireland 2016). The Community Childcare Subvention Resettlement (Transitional) CCSR (T) was introduced by the Department of Children and Youth Affairs in 2018 and in collaboration with Focus Ireland provides free access to free childcare for families experiencing homelessness for up to five hours per day with a hot meal included (DCYA 2018).

While not originally included in the Action Plan For Housing and Homelessness, family supported accommodation or family hubs were also introduced in 2017 as an alternative to unsustainable and less stable emergency accommodation such as hotels and B&BS.

2.6 Policies and Perspectives in Early Years Care and Education

Following ratification of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child in 1992, Ireland made a commitment to respect, protect and fulfil childrens rights including the right to a standard of living adequate to the child’s physical, mental, spiritual, moral and social development (article 27). Commitments within the programme for Government (2011) included, the referendum on childrens rights, the establishment of Tusla the child and family agency and the establishment of the Department of Children and Youth Affairs (DCYA) presenting improved integrated services directed at the early years which are also based on research evidence reporting positive outcomes for children (Institute of Public Health and the Centre for Effective Services 2016).

A distinctive element of recent policy development in relation to early childhood in Ireland is prevention and early intervention work underpinned by Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory. Considering the diverse influences on development and adaption highlights how a multidimensional approach to working with young children may be the most appropriate. The ecological framework may be a useful perspective from which to examine the adaptation of children and families experiencing homelessness and to examine the basis for system responses (Kilmer, Cook, Crusto, Strater & Haber 2012, Institute of Public Health in Ireland and the Centre for Effective Services 2016). Early childhood is acknowledged as critical period where with good nutrition, adequate housing secure relationships and safe learning environments, the development of child health and well being can be achieved. However adverse childhood experiences such as poverty, abuse and neglect may negatively impact child health and wellbeing and also a wide range of future outcomes. Early intervention has been identified as key to achieving positive outcomes within Better Outcomes Brighter Futures: The national policy framework for children and young people 2014-2020 and Healthy Ireland: A framework for improved health and wellbeing 2013-2025. Following investment from the Atlantic Philanthropies 52 prevention and early intervention programmes which were rigorously evaluated provide evidence of the positive impact of early intervention during early childhood. (Institute of Public Health in Ireland and the Centre for Effective Services 2016). Right from the Start: Report of the Expert Advisory Group on the Early Years Strategy focusing on children up to six years old identified five key areas that needed to be addressed to improve resources for young children including increased investment in early care and education, extended paid parental leave, strengthened family support, good governance and accountability and quality in services, enhancement and extension of quality childhood care and education services. First five A Whole of Government Strategy for Babies, Young Children and their Families 2019-2028 proposes commitment to a ten year plan to support children and their families making a huge contribution to the lives of young children, society and the economy over the short medium and long term. Included in this plan are measures to address poverty in early childhood including a DEIS type model for early years to narrow the gap for disadvantaged children (Government of Ireland 2018).

2.7 Implications For Provision Of Early Years Care and Education

Current provision of early years care and education occurs in a dynamic environment shaped by continuing policy changes and developments impacting on accessibility and types of provision. Current funding programmes implemented by the DCYA have provided access for 185,580 children to services during the 2017/2018 programme year. Furthermore two additional strands of CCS, CCSR and CCSRT provided access to 530 refugees and children of families experiencing homelessness (Pobal 2018). The National Childcare Scheme, which launches in October 2019, proposes to replace all targeted programmes with a single streamlined scheme enabling some families to access childcare subsidies for the first time (NCS 2019).

Further programmes aimed at supporting service provision and enhancing quality, include Better Start, Access and Inclusion Model (AIM), capital funding, the Learner fund and the Area-Based Childhood Programme (ABC) (Pobal 2018). While there are a range of services within both private and community sectors, using a varied curricula and quality standard approaches, Aistear is the most widely applied curriculum framework and the Síolta framework sets out quality standards. Both are used in the majority, also with the proportion of services applying the frameworks broadly similar across community and private services promoting a consistent approach.

Notwithstanding the complement of supports to early years care and education provision some services have more access to certain supports than others. In relation to the current 13 ABC sites while it was found that these programmes supported achievement of outcomes in select communities other communities which may have equally benefitted are excluded. This is an important observation given that highly mobile families who are experiencing homelessness may move between a number of communities. Families who are homeless face challenges in relation to parenting in relation to forming healthy emotional and social attachments with their children, developing safe and nurturing environments and developing links to family supports which can empower the family (Swick and Williams 2010). Moreover, parents who participated in interventions within ABC programmes reported that they had change in level of perceived empowerment and confidence feeling better to set boundaries and discipline their children. They also had developed informal peer networks and increased knowledge and confidence engaging in local services (DCYA 2018). Therefore these supports are highly relevant to parents who are homeless when it is proposed that their relationship with their children is the core element at the centre of their efforts to resolve their challenges (Swick, Williams & Fields 2014). The recently launched First five (Early Years) strategy proposes the development of family and early childhood centres bringing together a range of services to support children and parents which will further modify service provision (Government of Ireland 2019).

2.8 Leadership

While considering services within the ecological framework the role of the manager is observed as working within the micro system with children, families and staff, while moving within the meso system as they engage with inspectors, funders and collaborating agencies also encountering legislators within the macro system. They manage challenges that may arise within and between the systems and among relationships of others within the systems, implementing the numerous initiatives under legislative frameworks while ensuring sustainability and quality service which meets the needs of services users (Moloney & Pettersen 2017). As a result the managers role is consequently evolving becoming more complex providing the link between policy and practice. Building leadership capacity is recognised as vital to ensuring development of solid reciprocal relationships between theory and practice. It is therefore beneficial for managers to be aware of their role as agents of change and the skills and leadership styles required to assume this role successfully (Urban, Vandenbroeck et al 2011). Effective management requires the ability to prepare and motivate practitioners for change confirming confidence in their capability to meet new requirements (Rodd 2013). Competence in cultural analysis is required if they are to lead change. As managers lead staff towards evidence based practices they may need to explore understand and challenge embedded values and assumptions while also understanding cultures existing within collaborating agencies which also support children and families (Schein 2010).

While the quality of early childhood care and education is related to the competence of the practitioners working with the children and families, competence can be understood as a characteristic of an entire early childhood system. Within a competent system support is required for practitioners to realise capabilities to develop responsible and responsive practices to children and families within a continuous changing societal context. (Urban, Vandenbroeck et al 2011). Accessing supports for staff is therefore a crucial element to the managers role in retaining qualified staff by providing opportunities for continuous professional development and improving working conditions. Engaging in joint learning and critical reflection will enable the development of reflective competencies supporting work within diverse and changing contexts. While improvement in qualifications, training and working conditions are identified as a crucial element of an effective policy lever for improving quality (OECD 2012), it is worth noting that the employment levels for graduates is currently at 22% of the workforce (Pobal 2018) which is comparatively low in contrast to the European recommended level of 60% of a graduate led workforce (Urban, Vandenbroeck et al 2011) A feature of this is the risk that poor salaries may make staff retention a concern and a challenge for many managers, who can struggle to employ suitably qualified and experienced early years professionals.

2.9 Conclusion

The following chapter will present findings in relation to managers responses following semi structured interviews carried out within a three week period in January 2019.

Methodology

3.1Introduction

This chapter provides an outline of the research methods chosen and describes the research design. Details in relation to the sample are outlined followed by data collection and data analysis applied. Ethical considerations and limitations are presented.

3.2 Research Approach

Due to the exploratory nature of this study a qualitative paradigm was adopted. Exploring how social phenomena arise in the interactions of the respondents indicates a qualitative approach is more appropriate, with quantitative methods being more useful for establishing social facts or the causes of the phenomena (Silverman 2017). Positioned within a constructionist ontology the researcher views the social world as social constructions being constructed through individual’s perceptions and their interactions with others (Denscombe 2010). The research is guided by an interpretivist epistemology where it is understood that social reality has meaning for individuals and in turn attributes meaning to their actions. Individuals then act upon the meanings that they attribute to their own actions and the actions of others. The research interprets their actions and their social world from their point of view (Bryman 2016).

Data collected within a qualitative paradigm that is text, words and images are better suited than data in numbers associated with quantitative paradigms, in gaining an understanding of the complexities and subtleties of the social world. Qualitative research allows the research to gain an insight to into the meanings that people give to a social phenomena from their point of view (Denscombe 2010). A qualitative approach for this research will allow exploration of the perspectives of early years managers in relation to their service responding to the phenomena of family homelessness and the increase in numbers of children attending services who are homeless.

Qualitative research is particularly appropriate to studying context, illuminating process including organizational change and decision making which in turn affect daily practice and interactions. Unintentional consequences or responses to change may be uncovered during qualitative research as respondents identify issues significant to them and how they affect their daily work practices (Barbour 2014). This research concerns response to change and the decisions that have to be made around this change by early years services which makes it well suited.

Unlike quantitative research qualitative research highlights how the macro such as social class or locality is interpreted in the micro that is daily practices and interactions to guide individual behaviour (Barbour 2014). Qualitative research provides a rich account of how Early Years services interact and respond to features of the macro in relation to the context in which they are situated and the policy applicable to the early years service and the children and families who use the early years service.

A recent study in an Irish context in relation to the educational needs of children experiencing homelessness and living in emergency accommodation (Scanlon & Mc Kenna 2018) reported a low response rate by early years services to questionnaires, resulting in quantitative data being omitted. It was decided that given the time limitations for this study that a qualitative approach would allow for a more accessible and richer sample.

3.3 Research Instrument

Data for this research was collected using semi structured interviews where by using a protocol (see appendix 1), questions were arranged to allow systematic collection of data with the aim that the focus provided would also facilitate analysis of the data. Although the interview protocol included prearranged complete questions it was also possible to encourage the respondents to speak personally and at length about their experiences. The research while exploring a number of topics to uncover the respondents views respected how they framed and structured their responses. Semi structured interviews allows a large quantity of data to be gathered quickly with immediate clarification and follow up possible. However it is necessary to consider the importance of building trust and rapport with respondents ensuring they are comfortable answering questions and can do so providing the information or data required. The research is relying on the respondents ability to articulate their responses and the researcher must be able to understand and interpret them (Marshall & Rossman 2016). The researcher will also be aware that large quantities of data collected during interviews will need to be transcribed which may be a lengthy process impacting on time frames. Data was collected over a period of three weeks.

3.4 Sample and Access

3.4.1 Sample

The sample was comprised of six individual early years professionals in management roles within six early years settings in five different urban areas of Dublin. Five of the settings were community based early years services, three of which are full day services and two of which are sessional services. One respondent worked in a private full day service. All respondents had a number of children attending the service who were experiencing homelessness. Two of these services were set up specifically to meet the needs of children who were experiencing homelessness. In relation to one of the interviews conducted it must be noted that two managers from the same service were present and while one manager was the main respondent both responses were transcribed and presented in the findings. During the course of the research a network meeting for early years professionals was attended by the researcher and two additional respondents were invited to participate in the study. One respondent was the manager of a community based service and who had a number of children attending their service who were experiencing homelessness. The second additional respondent is employed by a Government funded company in a supporting role to early years providers. This respondent presented a recent brief within their role to develop links between staff and families placed within emergency accommodation such as hubs and hotels with early years services in the community. One particular objective within the brief was to highlight a childcare funding initiative specifically for children who are experiencing homelessness.

3.4.2 Sampling method

When the focus of a study is on a particular population a specific strategy should be developed in relation to that population that is conceptually or theoretically informed and will guide the researcher in making the many sampling decisions that will follow (Marshall & Rossman 2016).

A non-probability form of sampling, purposive sampling was used for this research project as the sample chosen were relevant to the research question and met the criteria in that they were in a managerial role within an early years service which had a number of children attending the service who were experiencing homelessness (Bryman 2016). The sample size is determined by a number of factors including time constraints and funding with the purpose of the study of most concern. While larger samples including more diverse respondents and settings might enhance transferability of the findings smaller samples provide data with deeper cultural descriptions (Marshall & Rossman 2016). Six Services were identified from a list of services on the Dublin City Childcare Committee data base and listed as offering a variety of government childcare funding options for service users. The rationale for considering services offering a variety of funding schemes was that it would be likely that these services who would have a good mix of children from different socio economic backgrounds that is children availing of the universal two year free preschool years and children availing of funding for families on lower incomes and families experiencing homelessness. Six respondents were initially contacted by phone followed by emailing a letter of information and invitation to participate in the study. Two respondents were recruited following the researchers attendance at a child care providers network meeting hosted by the Dublin City Childcare Committee where they were approached and verbally informed of the study and invited to participate. They were sent by email the same letter of information and invitation. The information letter gives respondents details of the research and a sense of if they are a right fit for the study. Gatekeepers for organizations will be required to carefully consider invitations to participate in research so a detailed account will facilitate their decision and allay possible hesitations (Marshall and Rossman 2016).

3.4.3 Rational for target population

Early years service managers were selected for the sample as they are responsible for ensuring that the service they are providing is meeting the needs of the children and families using the service. They also have responsibility to ensure that the service complies with the relevant legislation and fulfils contractual agreement in relation to Government funding. They are in the most appropriate position to observe the changing needs of children and how current policy provides for the service meeting these needs.

3.5 Data Collection

Following the respondents agreement to participate in the study appointments were set to meet and carry out the semi structured interviews in the respondents place of work. One respondent requested an alternative location due to their working arrangements away from their usual place of work on the day that suited them best. This was facilitated in an office space at the researcher’s place of work due to the convenient location for the respondent.

Before each interview respondents reviewed the letter of information regarding the study and signed a consent form. Respondents were reminded of their right to choose not to answer questions if they did not wish to and their right to withdraw from the study at any stage. Opening questions allowed participants to feel at ease and were followed by content questions and probing questions to deconstruct the central phenomenon being explored. Participants were invited to ask questions provide additional relevant information or information they may have omitted in an earlier response during the closing instructions (Creswell & Creswell 2018). Interviews lasted 15 mins -1hour 20 mins and took place in the participant’s usual place of work. They were digitally recorded on a password protected recording device. Recordings where transcribed and saved in an encrypted file on a password protected device.

3.6 Limitations

Qualitative research, while providing extensive rich data is time consuming to prepare for analysis. During the process of transcribing interviews the responses become very familiar facilitating analysis. However transcription is an interpretive process and some context might be lost changing from one medium to the next. The feel of the interview session may not be captured as transcripts may not convey setting context and body language (Neuman 2011). Given the small sample size findings cannot be generalised to the experiences of all early years managers providing a service meeting the needs of children experiencing homelessness. Furthermore the sample is not evenly distributed across types of early years provision such as community, private, or part of wider organisations.

3.7 Ethical Issues

Awareness of the ethical issues that may arise during research facilitates informed decisions about the implications of certain choices (Bryman 2016). Informed decisions will allow the interests of the participants to be protected and ensures that their participation takes place under informed consent. Deception is avoided and integrity of the research is supported while complying with the law of the land (Denscombe 2010). Research ethics approval was approved by Technical University (TU) Dublin.

Ethical issues were anticipated prior to and addressed at each stage of the study that is at the beginning of the study, during data collection, analysis and reporting and also in relation to sharing and secure storage of information (Creswell & Creswell 2018).

By ensuring that all relevant information was presented in relation to what was going to occur during the study in a manner that enabled the respondent to fully comprehend the information and agree to voluntary participation, informed consent by respondents was obtained (Denscombe 2010) . Respondents were provided with an information letter in relation to the study and informed of their rights to anonymity, confidentiality and their right to withdraw their participation at any stage of the research project. (See appendix 3). All participants signed a consent form (see appendix 4).

Privacy was respected by providing anonymity which allows the social picture of the respondents to be provided without identifying information such as real name and location. This was ensured by assigning codes to identify respondents. Some respondents unintentionally included identifying information within their interview responses but these details were kept in confidence and stored securely by encryption (Neuman 2011).

3.8 Reflexivity

Reflexivity is used to promote validity of the research whereby bias is clarified and it is acknowledged that interpretations may be shaped by the background of the researcher in relation to gender culture, history and socioeconomic origin (Creswell & Creswell 2018).

As the researcher is currently employed within a service providing support to children and families experiencing homelessness it is acknowledged that respondents experiences were the focus of the study and that they may be very different. Another consideration in relation to the researchers employment experience is that some respondents may be hesitant with responses if they feel the researcher may hold more knowledge in relation to the topic.

As a number of respondents recounted stories in relation to families experiencing homelessness it was important for the researcher not to over empathise or get too drawn in and loose focus of the research. Given the sensitive nature and on closer examination the extent of the issue it is important to remain professional yet understanding.

At times respondents referred to other services and supports which may have been known to the researcher and this highlighted how the researcher needed to be very aware of confidentiality while engaging with the respondents and recording the responses.

It was noted during the interview process that a number of the respondents were very experienced within the Early childhood Care and Education sector and operating very well established services where it may be possible that respondents could assume that the researcher was familiar with all the services that they provide and omit certain information.

3.9 Data Analysis

Analysis allows us to improve understanding, expand theory and advance knowledge (Neuman 2011 p.507) By organizing data systematically integrating and examining, patterns and relationships are found with concepts and broad themes are identified (Neuman 2011). Data analysis was guided by Braun and Clarke’s (2006) six steps approach to thematic analysis which facilitates organization and description of data concisely in rich detail often interpreting various aspects of the research topic.

The interviews were transcribed which allowed for familiarization with and thorough understanding of the data. Care was taken during this process as changing the medium of the data may have implications for accuracy, fidelity and interpretation (Gibbs 2013). Respondents were assigned codes (R1 to R8) to ensure anonymity and any identifying information in relation to children, families, staff and the service were omitted from the text. Ideas and potential coding schemes were noted throughout this process. During the second step Initial ideas or codes were generated manually in relation to data that was interesting or meaningful and that had related to the literature review. Codes went beyond the descriptive being analytic and as theoretical as possible (Gibbs 2013) Highlighters were used to colour code potential patterns noting that some responses were highlighted in a number of colours as they may correspond to a number of potential themes. These codes were then collated together and ready for the next step of identifying a number of codes that could combine under an overarching theme and arranging the codes under these potential themes. Reviewing these themes helped refine choice of themes in that some did not form a complete theme and where some themes needed to be further broken down. For the next step themes are defined and refined and sub themes developed. Extracts from the data were arranged under the related themes in a coherent and consistent account providing a narrative about what makes them interesting and how they relate to the overall story and the research question. Finally the report was written up providing an account of the story that the data has to tell (Braun & Clarke 2006).

3.10 Conclusion

Semi structured interviews provide flexibility in that the order in which questions are asked may be strategically arranged or prioritised by importance by the research while allowing respondents to focus or elaborate on issues that hold importance to them (Barbour 2014).

The goal of qualitative data analysis is to organise specific details into a coherent picture, model or set of tightly interlocked concepts (Neuman 2011p.509). The next chapter will present the findings from the responses in a coherent account.

Presentation of Findings

4.1 Introduction

This chapter presents data that emerged during eight semi structured interviews which were undertaken within a three week period January 2019. Data presented includes findings that emerged from seven semi structured interviews which were carried out with managers of early years services. In addition findings which emerged from one semi structured interview with a development officer for a Government sponsored company providing support to early years providers is also presented.

The data gathered was organised and is presented under three overarching themes emerging from the responses.

The first theme relates to service providers experience of working with children and families who are experiencing homelessness. The second relates to access to resources and how this acts as both a support and a challenge to respondents. The third theme explores impact on services in particular relation to staff and the role of the manager.

The views of respondents are presented under the themes identified with a number of sub headings and direct quotes from transcripts. Quotes are represented in italics and specific abbreviations (R1 to R8) are used to attribute the quote without revealing identity of the respondent.

4.2 Engagement

All respondents who were managing early years services reported that they had a number of children attending their service who were experiencing homelessness. An overview of the number of children accessing the services is set out in table 1

Initial response from one respondent in relation to the number of children attending their early years service and experiencing homelessness had included school age children. Further clarification sought by the researcher established the number in relation to early years children and this is the figure presented in the findings.

While some respondents noted that the numbers of children experiencing homelessness attending their early years service fluctuates others have observed a steady increase in recent years.

Last year I think we had eighteen homeless families using the service. The year before

there was about seven. We had none the year before that. (R1)

4.2.1 Types of homeless accommodation.

Respondent’s descriptions of children who were experiencing homelessness attending their services convey that most were living in various types of temporary accommodation while a number of children and families are staying with other family members.

So while they’re they’re not living in B&B accommodation or they’re not

living in hostels or anything like that. They are effectively homeless because

they would have had a home and now they don’t have one anymore. (R7)

Respondents noted that some families are remaining in temporary accommodation longer than is intended due to the shortage of alternative accommodation.

It’s a short term accommodation so it’s technically six to nine months that

they could be with us […] Some of our families are here two years at the

moment, (R8)

Engagement has led to respondents achieving a deeper understanding of the issue of homelessness.

I had my own kinda preconceived notions of homelessness and I very much

tied it all up with addiction and em, addictions of various sorts and kind of

more associated it rough sleeping as opposed to what I actually saw then […].

(R5)

4.2.2 Impact of homelessness on children.

A number of respondents described the negative impact of homelessness on child development, highlighting a negative impact on emotional development. Respondents observed children being tired from travelling distances between accommodation to the service which can also be a factor for erratic attendance or absenteeism. The lack of adequate cooking facilities in some accommodations results in poor diet for some children.

A lot of the children are eating from take away cause there’s no cooking

facilities in the hotel rooms. So they’d come in without breakfast. (R1)

The absence of laundry facilities sometimes results in children wearing inadequate or damp clothing.

They come in dressed inappropriately so if it’s cold they might have something

light on or their clothes are damp where they’re not being dried properly.

(R1)

A number of respondents discussed trauma of being homeless itself while others discussed the trauma of experiences preceding homelessness, which could be described as contributory factors. Concern was expressed that trauma manifesting in behaviours normally associated with a number of disorders possibly leading to misdiagnosis.

We’re concerned that when these children go into the school system are they

going to start getting diagnosed with ADHD em, when all they need is a bit of

space. (R7)

4.2.3 Contributory factors.

Respondents acknowledged that there could be numerous reasons why families are experiencing homelessness.

Being homeless itself is such a trauma, but the other bits that go on as well,

addiction, mental health everything that’s attached to it that most of our

families are dealing with […] (R8)

Highlighted by one respondent (R5) subsequent to visiting twelve family hubs, is a cohort of young women who had to leave the family home following the birth of their child.

[…] So young girls kind of the seventeen to twenty five who em maybe have a

child, maybe have a second child and due to overcrowding facilities in their

parental home […] (R5)

A number of respondents expressed the view that needs of children in homeless accommodation had become more complex presenting challenging behaviour, anger, anxiety and children appearing withdrawn.

There’s a crossover of children in the population. Children of homelessness

and children that are at risk…we are looking at children presenting with

challenging behaviour. We’re looking at children that are more at higher risk

of neglect or any other forms of abuse, emotional, sexual, physical. But

neglect would be the biggest thing. (R4)

4.2.4 Stigma, fear and isolation.

Respondents discussed that it can take time for parents to reveal that they have become homeless. In some cases a change is often initially noted in the child’s behaviour.

And it might take a few weeks but you’ll tease it out. You’ll find out well

actually they’re not living at home anymore or we’ve had to move in with my

parents. (R7)

Respondents reported how some families expressed fear and have experienced racism. Parents find it challenging to prepare food from their culture and there are language barriers to overcome which impact on professional relationships and obtaining necessary support.

Mum and dad take it in turns to stay awake to keep the children safe because

they don’t feel safe in the B&B. When they go down to use the kitchen they’re

being called terrorists because they are Muslim (R7)

Accounts suggest that parents worry about their future. Parents find it challenging to retain their employment while living in homeless accommodation as some accommodations do not permit visitors restricting the use of babysitters while working late shifts. Availing of education opportunities and supports is a challenge.

She had to take time off work because of all the other issues that were going

on. So there was loads going on in her life so she was like I have no money

[…] she was just so low. (R2)

[…], while the families are living in homeless accommodation it’s very hard to

commit and to participate either in the parenting course because they struggle

on an everyday basis. They need to go there and there. They are looking for

their accommodation. (R6)

One respondent acknowledged that families while living within supported housing accommodation, although they may become part of a community within the gated accommodation, with a strict no visitor policy, they may find it challenging to connect with the wider community, with limited access to friends and family leading to potential isolation. (R7) This was a similar experience for another parent residing in a hotel room.

[…] they can’t bring anyone into the apartment […] if they make friends with

the girl in the room next door they’re not allowed to go in out of each other’s

apartments because the cameras are in the corridors and they’re watching

(R1)

Parenting capacity is being undermined while families reside in emergency accommodation due to lack of space and noise restrictions where families may be reported if their child is upset or having a temper tantrum. Parent child relationships may be negatively affected by parents preoccupation in relation to accessing accommodation.

[…] mam being stressed out and running around and I don’t think mam was

fully there with her when she was with her. (R2)

4.3 Service Provision

Service provision was discussed in relation to resources, funding and staffing which increase organisational capacity to meet the needs of children and families. Particular issues relating to service provision included the availability of supports for children in relation to social and emotional development, conflict resolution and making choices while the need to provide supports for parents in relation to education and developing skills which promote positive relationships with their children was also identified.

4.3.1 Resources.

It appeared that some services had more access to resources that would enhance service provision for families. Services in areas of designated areas of disadvantage with access to ABC programmes had access to a variety of supports including funding for training for staff in Highscope, Circle of security and Infant mental health with enhanced access to an early years mentor and additional equipment. For some, being located in an area with a number of other services who are trained in the same approaches allows for consistency and continuity if children transition from one service to another. A number of respondents referred to an infant mental health network and an early years network as a source of support.

The services in […] really work well together at that community aspect in

helping each other out with it cause they’re all facing the same difficulties.

(R8)

In relation to services operating as part of larger organisations one respondent discussed how being the point of contact can connect the child and family onto further supports within the organisation.

Once you build that relationship with the parent then you can really refer

them onto other services that could support them further so for example

parenting courses or sometimes after that then counselling. (R6)

It was also highlighted how early years services can be an important link between families in emergency accommodation and services within the community.

That child has got to four without engagement in services […] it’s [early years

service] a life line for her (R5)

It emerged from accounts that some services were going beyond the expected level of service provision to support children and families in what ways they could.

He was really sick for a few days and we actually recommended she bring him

to A&E…we actually organised to gather up all the other children and we

kept them here until six o’ clock that day (R7)

..They [DCYA] say five hours a day but we’re open six so I let the children

[experiencing homelessness] come in […] at nine until three (R1)

We do give some food parcels and that to some of the parents that are

homeless. (R3)

4.3.2 Statutory funding.

Respondents referred to childcare funding schemes implemented by the Department of Children and Youth Affairs (DCYA). While the CCSRT scheme is welcome and is accessed, it often does not meet the needs of the children.

That’s only five hours a day […]parents need the full day cause they’re

working part time and spending the rest of the afternoon trying to figure out

like where they’re going to go.(R2)

In contrast to this, one respondent recounted having to negotiate access to CCSRT funding on behalf of the child as the service only operated twenty hours per week instead of the stipulated twenty five. (R6)

Maintaining access and provision is a challenge particularly for highly mobile families with regular appointments for supports or therapies, and long commutes to the service.

We have families […] and we are lucky to have them here. And they are being

policed and then their funding was cut. If they’re late in late out or early

leaving it all gets cut back. (R3B).

Furthermore respondents conveyed how professional relationships with parents may be compromised as they regularly address issues in relation to time keeping and absenteeism.

In some cases CCSRT hindered access to supports which were a feature of other funding schemes.

[…] Better Start Aim funding for the child with the diagnosis we couldn’t get

it because DCYA and Pobal came back and says no. She wasn’t entitled to

another year under the ECCE programme. (R4)

4.3.3 Staffing.

A relationship between Staff qualifications, continuous professional development (CPD) and quality was indicated by responses.

Our room leaders are a level 8 or a level 9 […] our room leaders work in our

breakfast service and our afterschool service. So there is a real good level of

quality in the service (R7)

4.4 Impact on staff.

While working with a diverse range of families respondents acknowledged that staff have adapted their practice to meet the needs of children and families accessing services.

I find they’re [staff] doing more of the day to day support with parents and I

am doing the bigger piece (R1)

When the family comes you’re supporting them because you’re having to give

them the time to chat with them. You know you’re giving them advice […]

(R7)

4.4.1Emotional cost.

Respondents expressed huge empathy for children and families experiencing homelessness.

I have parents here that would be very emotional, would be going through a

lot of stuff and then they’re trying to hide it from the kids but they’re, they

need someone. They haven’t got that support outside (R2)

We’re dealing with the parents also. But there are days when some parents

are feeling so low that they can’t even get a child in. They can’t hardly get

themselves out of the bed sometimes because they’re feeling so low. (R3A).

Changing needs of children and families places extra demands on staff on an emotional level.

Staff need something there to to because they’re going home worried sick

about the children (R1)

4.4.2 Changing manager role.

Managing change was conveyed as a feature of the managers role in supporting staff to understand and implement change to meet the complex needs of children and families. Respondents discussed how training enabled them to support the staff in relation to change.

So I felt my job became much easier with the backup of Highscope […] I’m

trying to use the staff to facilitate a lot of stuff because it’s it’s bringing the

staff up to another level as well. (R1)

They delivered workshops for our parents on healthy eating and they were a

bag of nerves the two of them and I said no you’ll be able to do it, you’ll be

great and the two of them done it and at the end of it the two of them said […]

I would never have pushed meself to do anything like that but they done it.

(R1)

Respondents expressed frustration in relation to excessive periods of time spent on administration duties in relation to funding schemes which are frequently accessed by children experiencing homelessness, limiting their time spent with children and families. Record keeping was discussed as becoming more extensive due to the complex support needs of the children and families.

Another role would be around that you have like a case management file so

that’s would have been new to me when I started here ten years ago […] (R4)

It was conveyed that managers are conscious of increasing workloads and the impact that might have on service provision.

I am managing the centre but I find I am getting pulled away more for

counselling work than I am for the day to day running of the service and it’s a

huge service so like it’s easy to miss something if you’re not on the ball. (R1)

4.4.3 Changing role of early years service.

Further to change in roles of staff and managers, it was proposed by respondents that the role of the early years service has evolved where now it supports the whole family and support is required to fulfil these roles.

We are seen as a protector factor now with the, with the social workers. (R4)

[…] when do you say we’re not a childcare service anymore? We’re actually

a family centre that’s catering for all these needs that’s not in our job

descriptions. (R1)

4.5 Conclusion

The three broad themes emerging from the responses will be discussed in the next chapter in relation to the research questions and current literature.

Discussion and Recommendations

5.1 Introduction

This chapter will focus on the three broad themes that emerged from the findings which are engagement, service provision and impact on staff. These are discussed in detail in the context of existing literature.

Current and statistics suggest that families and children are the fastest growing population of homeless in Ireland (Scanlon & Mc Kenna 2018, Department of Housing, Planning and Local Government 2018), and this is reflected in early years services, as respondents report an increase in numbers of children experiencing homelessness attending their services. This changing homeless dynamic impacts on how children and families engage with early years services. It provokes responses by early years services where in order to meet the needs of children and families experiencing homeless approaches may have to be adapted and changed to meet consequential challenges placed on the service.

5.2 Engagement

While the level of engagement with children experiencing homelessness was quite varied, accounts of experiences suggest a heightened understanding among respondents in relation to pathways into and the impact of homelessness on young children.

5.2.1 Pathways to homelessness.